Washington’s New State Capital Gains Tax

After two years of waiting, Washington has a new tax. Last week, the state Supreme Court ruled 7-2 in favor of the new 7% tax on capital gains. At issue was whether it was an income tax or an excise tax.

HOW THE NEW TAX APPLIES

Before you panic, note that the new tax probably doesn’t apply to you. The 7% tax applies to capital gains of more than $250,000 in a year AND it doesn’t apply to a host of capital gain-producing transactions. That’s a GAIN of more than $250,000, not the proceeds you received.

EXAMPLE: You bought Amazon (AMZN) stock at $100/share five years ago, and sold it for $150 last June. You sold 5,000 shares:

Capital Gain = Proceeds on sale – the cost of your original investment.

($150 x 5,000) – ($100 x 5,000) = $250,000 capital gain -> NO TAX

If you had sold 1 more share of stock, you would have an additional gain of $50 and the Washington Capital Gains Tax would be $3.50 ($50 x 7% = $3.50).

(Note the total proceeds to you in this example is $750,000. And no capital gains tax due.)

WHAT IS A CAPITAL GAIN IN WASHINGTON?

For purposes of the new state tax, “Washington Capital Gains” start with the capital gain reported on your federal return, then adjusts for things like:

• All real estate

• Retirement accounts

• Property used in a trade or business

• Sale of a family-owned small business

• Because it’s the West and it’s Washington: Timber, fishing privileges, cattle, horses and other livestock sold by farmers and ranchers

• And just because, goodwill from franchised auto dealerships.

The new tax does NOT apply to sale of your home.

…it does NOT apply to sale of your business.

…it does NOT apply to vesting of your RSUs.

…it does not apply to Roth conversions or distributions from your retirement accounts.

…it does not apply to a gain even if it is ABOVE $250,000 if it is short-term (you held the investment less than a year).

It DOES apply to large long-term profits in big portfolios.

If you are hanging on to company stock that has vested and need any extra incentive to divest, the new tax might be that.

IF THE TAX APPLIES TO YOU

The tax took effect on January 1, 2022 and if it applies to you, you have to file a tax return with the state Department of Revenue (DOR) by April 18, 2023, same filing deadline as your federal return this year.

The DOR’s Guide to the new Capital Gains Tax Return is available here.

The tax is expected to raise about $500 million annually for childcare, early learning, and K-12 education.

TWO YEARS IN THE MAKING

In April 2021, the Washington legislature passed ESSB 5096, signed by Governor Inslee in May of that year, which set a new 7% tax on capital gains starting in 2022, and which also started a string of lawsuits and appeals to overturn it. As of last summer, even the Washington State Department of Revenue (DOR) didn’t think the new law would survive the legal attacks on it. We started the 2022 tax season with the tax due on April 18, 2023 and no forms on which to file it.

Earlier this year as tax season began, the DOR issued an update about HOW to file, given that the appeal of the new law was granted a stay, meaning it would continue to be in effect even if it might later be overturned. The DOR still needed to administer the tax and collect payments, and they later clarified the reporting while we waited for the final say from the state Supreme Court. That online payment system was made available to taxpayers and their tax preparers in February to report and pay the tax.

THE SUPREME DEBATE

The debate over the capital gains tax reached the state Supreme Court in late January. Those arguing against the tax called it an income tax, which must be applied evenly across the same class of property under the state Constitution, and on all property equally, not just that above a certain threshold. The law called the new tax an excise tax on property, the same kind of tax you pay when you sell your house (currently 1.78% on the sale price of a home in Seattle).

A capital gain is the appreciation you enjoy when your investments rise in value. When you realize that growth by selling the investment, like a stock or bond, you have a capital gain to report. You can also have capital gains to report for a mutual fund, too, when the fund managers sell something in the portfolio that appreciated. That gain is passed along to the mutual fund investors at the end of the year.

Short-term capital gains are generated if you sell at a profit within a year of your original investment; these gains are taxed as ordinary income like your salary or pension, with no preferential tax treatment. Long-term capital gains are generated if you sell at a profit after holding your original investment for more than a year; the idea is to encourage long-term investment and so these gains are taxed at a lower rate. The top tax bracket for ordinary income in 2022 was 37%, the lowest tax on capital gains is 0%.

Some states conform with federal treatment of capital gains, taxing them at a significantly lower rate than income from work. Other states make their own rules. California for example – always the non-conformist – ignores the preferential federal tax treatment and applies ordinary income tax rates to long-term capital gains.

Washington, along with a handful of other states, does not tax its residents’ income (in theory). In fact, it’s in the state Constitution that only a flat tax on gross income or a tax of no more than 1% is allowed.

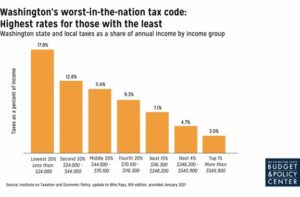

But all Washington residents are subject to a host of other taxes, from some of the highest sales taxes nationwide to excise taxes on the sale of a home to the new-in-2023 payroll tax to fund the state’s long-term care program, WA CARES. And businesses – including self-employed individuals – are taxed on their gross business revenue. The result is the most regressive tax structure of any state in the US.

TAX HISTORY IN WASHINGTON

The Washington tax code was not always this way. Following on the heels of statehood in 1889, the roads, schools and other infrastructure needed by a growing state required funding. Early legislators cobbled together language about tax on property that appears to have come from various other state constitutions (which sounds like our tax code was written by a nineteenth-century version of ChatGPT). As you might imagine, few people at the time had incomes in the sense we think of them today that could be measured and taxed, but many had property – land and farms – and so that became the base for the structure of our tax system.

STATEHOOD TO THE 1930s

The economy in the 1890s suffered through a depression and with land value depressed as part of it, state leaders went searching for new tax models to generate revenue, and settled on excise taxes. A couple of decades later, in 1913, the 16th Amendment to the US Constitution established a federal income tax and paved the way for states to implement the same. Washington voters tried multiple times to move to an income-based tax, most notably in 1933, when 70% of the state voted for an income tax. The many unemployed workers and farmers who lost their land to foreclosure in the Great Depression were looking for a way to share the tax burden. Pushback landed the proposed income tax in the state Supreme Court, which in 1933 decided Culliton v. Chase and invalidated the income tax despite the overwhelming support of voters. One researcher suggested that once the Supreme Court judges realized that the new tax would apply to their salaries, they found the income tax on individuals unconstitutional — but a tax on gross business income would be valid.

In response to the setback on a state income tax, the legislature proposed a business-and-occupation (B&O) tax intended to be temporary, and a sales tax as a back-up to that. Both taxes became permanent and together created the base of our tax structure today. The tax system that may have been suited for the state when it began did not produce the revenue needed as it grew. Instead of amending the state Constitution to support an income tax, a bevy of taxes on almost everything else emerged: taxes on gas and cigarettes, hotels and motels, rental properties – even pinball and slot machines.

THE 1970s TO THE 1990s

State revenue was strained in Washington and across the nation as the economy settled into a recession in the 1970s, and monkeying with the various and sundry taxes continued through downturns in the 1980s. By the 1990s, anti-tax lobbyists like Tim Eyman gained traction, ultimately only succeeding in briefly limiting the cost of your car tabs.

THE MILLENNIUM TO TODAY

The Millennium brought the dot-com boom and bust, and a few more attempts to shift the generation of revenue away from a regressive sales tax, with proposals like a Head Tax on Seattle workers in 2017 to help balance the new and extreme wealth in the same urban areas in which housing affordability and homelessness were growing issues. Amazon led the charge to strike down the Head Tax idea as a “job-killer.” Given the pandemic’s impact on working from home – and often not in Seattle – it would have been interesting to see how business’ push to return to offices would have played out if those employers could avoid the cost of a Head Tax by encouraging continued work from home.

And so this brings us to the next idea, the state Capital Gains Tax, upheld by the state Supreme Court and in effect for the 2022 tax year.

Next up in the Washington state tax evolution is a 1% Wealth Tax, proposed in 2023 by state Senator Noel Frame, on wealth above $250 million. Washington is part of a loose coalition of eight states proposing taxes on wealth to shift a greater portion of the tax burden to the ultra-wealthy. The only thing more challenging than figuring out how to value “wealth” on which to assess the tax will be getting past expected challenges to the constitutionality of the proposed tax.

You can read more on the new Washington Capital Gains Tax here, including instructions and videos on how to establish a capital gains account and file a return.