Inverted Yield Curves, the Next Recession, and You

I initially started this post two weeks ago, after we woke up to the news of Dayton and El Paso, which made it feel like the world was falling apart. That shock was followed by China’s devaluation of its currency, a different kind of shock, and the financial world seemed like it was falling apart, too.

By the time I’d finished a first draft that Monday morning and guessed that China would be labeled a currency manipulator, markets rebounded. And China was labeled a currency manipulator. Then came this last week, when we saw an inverted yield curve, and markets tanked again. By the end of the week, markets had recovered, and you were probably throwing your hands up or wishing there was a nice pile of sand into which to stick your head.

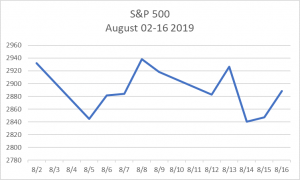

Let’s look at what happened to the stock market over the first two weeks of August when all this was going on, then we can talk about what was behind it. The S&P 500 tracks the largest US companies, and we’ll use that index here:

The first dip in the chart is China’s devaluation of its currency. The next, leading up to the plunge on Friday, August 9th, was related to squabbling over name-calling between the US and China, increasing tensions in Hong Kong when anti-government protests over a proposed extradition law turned violent, and the beginnings of investor flight from stocks to bonds. The sharp uptick of markets opening the following week on August 13th was a reaction to the Trump’s Administration’s announcement of a delay in implementing new tariffs on China from September until mid-December. News of the inverted yield curve came on the 14th, and markets collapsed. On Friday, Walmart’s quarterly earnings beat estimates, and that news along with other strong earnings numbers led to a rise in non-tech stocks.

So, yeah, if you’re feeling like following the ups and downs of the market is like playing whack-a-mole, you’d be right.

The big issues of a trade war with China and an overall flight to safety in financial markets are the two main things to watch, and we’ll take each in turn.

China’s Currency Devaluation

At the beginning of the month, the People’s Bank of China (PBOC) devalued the yuan, citing “unilateral and protectionist measures as well as the expectation of additional future tariffs on Chinese goods.” President Trump had threatened China with an additional 10% tariff on Chinese goods to go into effect in September, despite reported progress on trade.

When I was in grad school, even after studying economics in college and working in finance, taking an international investments class was like trying to think in an extra dimension. Supply and demand charts I understood. But now throw in the impact of multiple currencies? Until we all move to bitcoin, global commerce will still require an extra step: If I want to buy something made by someone using a different currency, first I have to buy some of their currency, then buy their product using their currency.

And let’s be clear: US importers and their US customers (i.e. you) pay the cost of the tariffs. China “pays” in that their exports are more expensive to offshore buyers.

When the US puts a tariff on Chinese goods, it costs more to buyers here to import their products. So your Chinese-made clothes and electronics become more expensive to the stores here. Those stores have to buy their products in the local currency (yuan). By lowering the exchange rate with the US dollar, the Chinese have made their products cheaper for US stores to buy. By devaluing the yuan, China essentially canceled out the effect of the US tariffs for its buyers.

This doesn’t sound so bad, right? I can buy a new iPhone or a new sweater for the same price to me (and profit to the US company) than I would have before our current trade kerfuffle began.

Yes…and no. That China devalued the yuan to immunize their exports from US tariffs also means they are taking a hard line with regard to trade talks.

Currency manipulation

My guess on what would happen next was that the US would label China a currency manipulator (which is true) and the President would double-down on an ineffective trade policy. I was three-quarters right. We’re experts at name-calling these days, and so China was called out for manipulating its currency. Financial markets reacted. The market wasn’t expecting the devaluation of the yuan or the uncertainties that come with it. Turmoil ensued.

You could make the case that the US manipulated the US dollar when we implemented Quantitative Easing (QE) during the financial crisis. At that time, we (the US government) bought our own Treasury securities, pumping millions of dollars into the economy. This flood of dollars drove interest rates down, and drove down the value of the dollar. Sound familiar?

The Federal Reserve, China and Leverage

The Fed’s main job is to manage inflation. To do this it serves as the gatekeeper for the flow of dollars in and out of the economy by changing interest rates (the Fed Funds rate specifically). The Fed decided to lower rates by 0.25% at the end of July. This cut was the first in a decade, and many in the financial world saw this move as politically motivated, anathema to the tradition of the central bank as an independent inflation watchdog, not the political pawn of an administration wanting to stay in power. Typically, interest rate cuts are used to stimulate the economy. But wait – we’re told the economy is “tremendous.” Why does it need stimulating?

One factor that seems to be left out of the trade mix is the heavy investment of China in the US. We have been financing our growing deficits by selling Treasury securities – and outside of the US, the largest owner of US Treasuries is China. The “nuclear option” in the trade war would be for China to start dumping US Treasuries. The dollar would collapse and interest rates would spike. Everyone says this would never happen, as it would hurt China too. Yet we live in unusual times, and brinkmanship can send both parties tumbling over a cliff. Our President is used to doing deals based on other people’s money, and he eventually will walk away from the Oval Office. What remains to be seen is whether the aftermath here will be similar to the multiple bankruptcies from which he has also walked away, leaving the mess for someone else.

And yet, we managed to wade through all that, with markets having recovered by the end of the first week of August. Then some fool noticed the inverted yield curve.

The Inverted Yield Curve

You think about yield curves even if you don’t realize it. When you’re deciding on a mortgage, you know that a 15-year loan comes with a lower interest rate than a 30-year loan: with the longer term mortgage, there is more risk to the lender that something might interfere with your ability to repay, and the money they’ll get back will be worth less with each passing year, thanks to inflation. What the lender is expecting to receive – the interest payments over the loan term – is the yield.

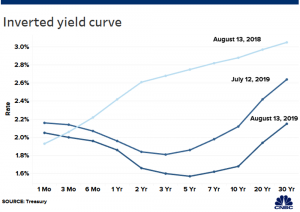

Each type of debt has its own yield curve, and a basic one for US Treasuries normally looks like this:

Normally, the longer you are asked to loan money, the more you’re going to expect in return. The yield curve typically shows how you need to pay more in interest the longer the period over which you borrow money. If you loan a friend $100 overnight, you might be fine with just getting the $100 the next day. If you loan them $100 for a year, you might be a little worried that you might not get it back. In addition, the $100 you get back in a year might not cover the cost of that bauble you’re planning to buy with it a year from now. You can’t be sure that the price of baubles won’t go up. Possible price increases equal inflation risk. And you want to be compensated for that risk, too.

The term structure of interest rates (the finance-fancy name for the chart above) shows how when you loan money, you want to be compensated for the decline in purchasing power of your loaned dollars (inflation), and for the risk that something will happen to interfere with repayment of the loan (default risk). Normally we expect short-term loans to have low interest rates, intermediate term loans higher rates, and long-term loans higher rates still.

But last week, the inverted yield curve showed the reverse: some longer-term loans had a lower interest rate than short-term loans:

How does that make sense?

To make it extra confusing, there is more than one reason why the yield curve might invert. When investors think a downturn is looming, they might want to hold longer-term bonds, and this demand causes the inversion. Another theory is that lenders have a reduced incentive to lend for the long term – they can make as much or more money lending in the short-term.

Even though the news reported that “this was the first time the yield curve inverted since 2007” (prior to the Financial Crisis), that’s not precisely true. Different parts of the yield curve have been inverted since then; in March the 10-year Treasury bond yield fell below the 3-month yield. What got everyone’s panties in a bunch this past week was that it was the two-month bond yield that pivoted higher than the 10-year bond yield.

Not many paid too much attention to the March inversion because the 3-month yield isn’t used as a benchmark in the same way as the 2-month. Going back to the mortgage example, most of us might note a change in the interest rate on 15-year or 30-year mortgages – those are industry benchmarks – but not care too much if the rate changed on a 20-year mortgage.

Does This Mean We’re Going to Have a Recession?

A yield curve shifts for a variety of reasons, but here the curve showed something akin to a herd phenomenon: investors wanted to move out of stocks (risk) and into bonds (safety). The reason an inverted yield curve is considered a sign of recession is because it signals an unwillingness to take risk, it shows a flight to safety. The media enthusiastically reported that “the yield curve has inverted before every U.S. recession since 1955”. But it tells us nothing about the timing of this next recession.

An inverted yield curve doesn’t “predict” recessions or downturns. It’s an indicator, a sign, that market participants watch. It’s important because markets are made up of people (and computers, but they are programmed by people). When people lose confidence, they choose safety over risk.

But remember, the same folks who look at “signs” to predict downturns completely missed this back in 2007 – and some of the same people also look at skirt hemlines and who wins the Super Bowl to predict future market behavior. An inverted yield curve might occur months or YEARS before a recession.

Which brings us back to what most economic forecasts have been saying (and which I relayed in my last Market Report to clients): it’s more likely than not that the US will move into a recessionary period sometime in the next year or two. With the uptick in trade tensions, we might be more on the short end of that range now.

Trade Tensions

As mentioned, when I started this post, the stock market had tanked on the news of the devaluation of the yuan.

Circling back to where we started the month, last week after the market downturn, President Trump decided to delay his now completely ineffective new tariffs – which he says don’t cost Americans anything – until after Christmas to help holiday shoppers. Markets responded favorably. Thanks, Santa.

What It Means for You

Between now and the Presidential Election, there will be noteworthy economic statistics and there will be bellowing and bluster. You need to listen for the noise in the numbers:

• The US unemployment rate is at a historic low – but not everyone is in a good job, with many taking on second jobs or “gigs” to make ends meet.

• Tax cuts were supposed to lift wages and stimulate the economy, but after an initial round of meager bonuses from a few big corporations, more individual taxpayers were left with a reduced tax refund – or tax due – in 2018.

• With the tax benefits to individual taxpayers skewed to the early years of the tax plan, you’ll likely see higher taxes in coming years – unless even more tax gimmicks are passed to prop up consumer spending today at a higher cost tomorrow. The latest chatter is a payroll tax cut.

• While there is a new school of Modern Money Theory (MMT) that says deficits don’t matter (Democrats like this theory to fund proposed social programs, the Republicans have applied it to pay for the big tax breaks to corporations and the ultra-wealthy), some of us think running deficits while you have a booming economy is woeful mismanagement.

When a recession does come, we won’t have the capacity to stimulate the economy with monetary policy through more rate cuts (because we will have lowered rates as low as they can go) or fiscal policy through spending on infrastructure projects, keeping people employed and getting improved assets in the bargain (because we will have maxed out our collective credit card, aka the national debt).

What you can do is tidy up your finances:

• If you’ve run down your cash reserves, make it a priority to build them back up.

• If you are still in the workforce, spend a weekend updating your resume and professional online presence; watch for opportunities to add to your portable career equity – those projects and skills that would be valuable to another employer, not just your current one.

• If you’re retired, review your “buckets,” the portions of your savings that are allocated for near-term and intermediate-term spending. Most clients will have 5-7 years of savings set aside in these buckets.

• Working or retired, if you’ve taken on debt – credit card balances, no-interest-until-sometime-later deals, draws on home equity and the like – look hard at repaying it as soon as you can, both reduce your monthly spending and to clear out borrowing capacity if you need it later.

Remember that the stock market is NOT the economy. With a cash reserve and “buckets” for near-term spending if you’re in retirement, you can ride out stock market fluctuations.

The stock market is also NOT your personal economy. Your personal economy is your household, and your ability to pull in enough income to cover your expenses. If you’ve diversified your investments, you won’t be beholden to the performance of one company or one sector to finance your life in the event a stock market decline hits some industries more than others. And if you’re working, you’re keeping your tools sharp and skills current in the event a downturn affects your company and your job.